Video:The Actual Reason to Brine Your Turkey: Science Explained

Just play the video directly and subtitle in your language will show up, if the subtitle is not in your language, you can go to youtube and use the subtitle function.

If you like my video, you can subscribe here for more interesting PAA.

For most Americans, the holiday and thanksgiving involve turkey roasting. And a lot of holiday turkey recipes recommend brining your turkey before roasting it.

And according to conventional wisdom and most recipes online, the process of bringing will make your turkey juicer!

I was suspicious about it a while ago when I first attempted to roast a turkey because while those recipe websites did their best try to explain the science behind brining your turkey or chicken before roasting, most of them are not very convincing.

For example, an article published on Thespruceeats.com titled “Brining Poultry for Flavor and Tenderness” said the following, which I don’t think is true:

When you place meat in a brine that has more salt than meat, the liquid will flow through the cell walls into the meat, which adds moisture.

Well…if you did pay attention to your middle school science class, you know the above quote is totally wrong.

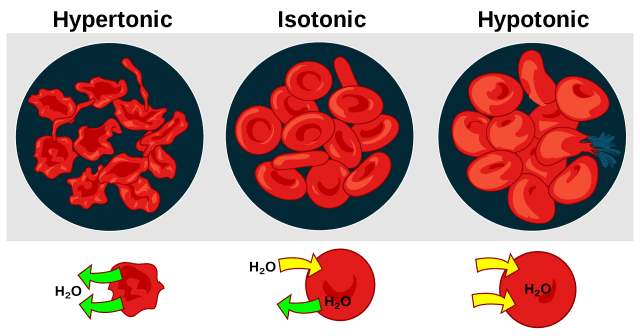

Just a reminder of the concept of tonicity:

Saltwater you use to brine your bird is typically considered a hypertonic solution because it has a greater concentration of solutes than the liquid found inside the cells.

When a cell is immersed in a hypertonic solution, osmotic pressure tends to force water to flow out of the cell instead of forcing water into the cell. What theoretically will happen is, actually, completely the opposite of what the article described.

So is bringing a turkey even worth the effort? Let’s find out with PAA!

Hi, I am Shao Chieh Lo, welcome to what people also ask, where I search something seemingly obvious and share with you some of its PAA, aka People Also Ask, which is a feature telling you what other people are searching on Google that relates to your query.

Today’s query is “What is the science behind brining a turkey?”

In today’s episode we will explore the following questions with PAAs:

- Is bringing a turkey worth the effort? Does it actually do anything?

- If brining actually work, what is the science behind brining a turkey or chicken?

So

Is bringing a turkey worth the effort?

I found an article that answers this question very well titled “The Actual Reason to Brine Your Turkey: It’s Not Osmosis”, published by…me.

So according to my article, Brining Actually Make Your Poultry Juicier And More Tender According to studies.

A research conducted by researchers at the University of Florida published in 1978 on Poultry Science applied three different treatments to broiler meat:

- marinating in water

- marinating in salted brine

- 3. no-marinating.

After cooking, the meat samples were evaluated for flavor, tenderness, and juiciness by a taste panel.

The result? While, all of them were scored favorably for flavor, tenderness, and juiciness, samples marinated in salted brine received higher scores than the other two.

Also, according to them, the meat brined in salted water had significantly higher moisture content and lower shear force values (Which is a fancy way to say it’s more tender) than meat marinated in water or meat that went through no marinating process.

Another research published in 1979 in the same journal also found that Salt brined chicken lost significantly less water during the first 24 hr post-treatment when compared with chicken marinated in water..

Since all of those research is done on chickens, I also did a simple experiment on turkey the other day and I can confirm it’s a real thing that brine turkey does taste significantly more tender and is juicier.

So that leads to our next question:

What is the science behind brining a turkey with salt water?

This question is answered by the aforementioned article and another article titled “The Right Way to Brine Turkey” published on Serious Eat written by J. Kenji López-Alt, who is the author of the book “The Food Lab: Better Home Cooking Through Science”, which is a very interesting book published in 2015 where Lopez-Alt uses the scientific method in the cookbook to improve popular American recipes and to explain the science of cooking.

Both articles debunked the osmosis theory of brining as we discussed at the beginning of the video.

According to López-Alt The osmosis theory is, in fact, incorrect. If that were true, then soaking a turkey in pure, unsalted water should be more effective than brining it in salt water, which we have already established is not the case.

To understand what’s actually going on, we should examine the structure of turkey muscles. Muscles are made up of long, bundled fibers, each one housed in a tough protein sheath. As the turkey heats, the proteins that make up this sheath will contract. This causes juices to be driven out of the meat , similar to when you squeeze a tube of toothpaste. Heat them much higher than 150°F (66°C) and you’ll get dry, stringy meat.

Salt reduces muscle shrinkage by dissolving part of the muscle proteins (mainly myosin). The muscle fibers relax, allowing them to absorb more moisture and, more importantly, not tighten as much when cooking, ensuring that more of that moisture remains in place as the turkey cooks.

This theory is supported by research published in Food Research International in 2005 conducted by a researcher at the University of Kentucky. The researchers applied salt water brining treatment on chicken and pork and found that brining produced an expansion of the myofibrils(which are rod-like units of a muscle cell), resulting in substantial swelling of muscle fibers, and enhanced water uptake and immobilization.

Does brining work better on chicken breast compared to drumsticks?

A research published in the Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture in 2000 conducted by researchers at the University of Kentucky and Kentucky State University found that,in some cases, after brining treatment, chicken Pectoralis major( which I believe is a fancy way to say chicken breast) seem has more structural change and is more extractable then chicken Gastrocnemius ( Which I believe it means drumsticks).

The researchers then implied that, this might explain the different water-imbibing abilities of white and red meat when processed with salt.

Which is great, cuz in my opinion white meat definitely needs more tendering up treatment then red meat.

So, how do you think? Do you brine your chicken or turkey before cooking it? What is the optimal concentration of brine when it comes to brining in your chicken or turkey?

If you made it to the end of the video, chances are that you enjoy learning what people also ask on Google. But let’s face it, reading PAA yourself will be a pain. So here’s the deal, I will do the reading for you and upload a video compiling some fun PAAs once a week, all you have to do is to hit the subscribe button and the bell icon so you won’t miss any PAA report that I compile. So just do it right now. Bye!

Photo Credit: nesson-marshall Flickr via Compfight cc

https://www.flickr.com/photos/45513305@N02/11781996593/

References:

- Janky, D. M., Arafa, A. S., Oblinger, J. L., Koburger, J. A., & Fletcher, D. L. (1978). Sensory, physical, and microbiological comparison of brine-chilled, water-chilled, and hot-packaged (no chill) broilers. Poultry Science, 57(2), 417–421.

- Carpenter, M. D., Janky, D. M., Arafa, A. S., Oblinger, J. L., & Koburger, J. A. (1979). The effect of salt brine chilling on driploss of ice-packed broiler carcasses. Poultry science, 58(2), 369–371.Chicago.

- Xiong, Y. L. (2005). Role of myofibrillar proteins in water-binding in brine-enhanced meats. Food Research International, 38(3), 281–287.

- Xiong, Y. L., Lou, X., Harmon, R. J., Wang, C., & Moody, W. G. (2000). Salt‐and pyrophosphate‐induced structural changes in myofibrils from chicken red and white muscles. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 80(8), 1176–1182.

*Disclosure: I only recommend products I would use myself or think would be helpful to my reader. This post may contain affiliate links that at no additional cost to you, I may earn a small commission.